Reflections on the London SciComm Symposium

The Cultural Contexts of Health project being developed by the University of Exeter WHO Collaborating Centre on Culture and Health in collaboration with WHO Europe aims to engage with a broad audience in order to explore how experiences of illness and medical knowledge are shaped by cultural practices and beliefs, both now and in the past. It is therefore important to reflect on what the foundations of meaningful engagement are and how this can benefit those we engage with as well as academics in the Centre.

I had the privilege of attending a London SciComm Symposium. The event attracted an exciting line-up of speakers from across the world of research communication and public engagement in the UK, including: Mary-Clare Hallsworth, Public Engagement Coordinator at Birkbeck; Steve Cross, Wellcome Engagement Fellow and formerly Head of Public Engagement at UCL (University College London); Kimberley Freeman, Executive Officer for Public Engagement, and Manager of the Centre for Public Engagement at Queen Mary University of London; Janet Stott, Deputy Director and Head of Public Engagement at Oxford University Museum of Natural History; and Dom Galliano, the director of outreach at South East Physics Network (SEPNet).

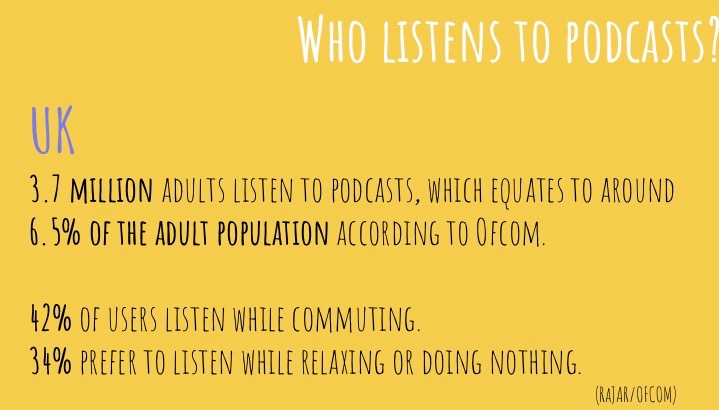

The symposium was framed around the formal and informal sides of research communication and looked at initiatives and activities currently underway in the field of engagement, and the relationships between researchers and science centres, festivals and their host universities. Speakers discussed activities which ranged from a ‘Science Show off act’ and a PhD student’s alter ego, Dr Jiggs Bosom, to communication mediums, such as Podcasts.

Image supplied by Emily Elias: www.tinyletter.com/emilyreports

The event ended with a look at diversity, specifically broadening the participation and audiences for engagement.

Engagement is a mutually beneficial process and the exchange of benefits is measurable

Professor Sophie Scott, a Neuroscientist from London, began working with impressionists as part of communicating her research on the neural basis of human speech processing. Professor Scott soon came to realise that there was a whole new area she could learn from impressionists on the voice, and began to produce scientific findings on speaking vs voices. This led her to working with beat boxers and then with comedians on non- verbal emotional vocalisations, particularly laughter. Professor Scott’s external collaborators are named co-authors on her publications.

Engagement with external groups needs to continue long after the project is finished

The talks touched upon an area which is less discussed in the field of engagement and far too often ignored in my experience. This is the area of engagement past the point at which your project finishes. Time and resources in the academic sector are all too often lacking, and this results in having a closed timeframe on projects and limitations on how that engagement can progress past this point. It can be argued that there is an ethical obligation to do this but as many of the speakers at the event noted, prioritising continuing engagement will deepen the research field as well as the translation into policy or impactful initiatives by continuing the iterative ‘engagement, research, impact cycle’.

The case for continuing relationships is strong and my thought for the day was that this should be embedded more fully into high-level strategic objectives.

Diversity in engagement is lacking

Dr Emily Dawson spoke of her research on how people engage with and learn about science, with an emphasis on equity and social justice. Emily’s current research explores how to disrupt, rather than reproduce, social disadvantages in relation to science education, engagement and communication. Over the past 10 years she has carried out research on science learning and engagement in a variety of settings including science centres, museums, scientific societies and schools.

Her talk looked at the differences between changing practice, on the one hand, and simply changing how we talk about things. The message was about assimilation aiding change and not framing diversity as a crusade, which risks alienating audiences as it becomes patronising and belittling. She finished her talk with a quote from the writer, feminist and civil right activist, Audre Lorde. Lorde was best known for using poetry as a tool for informing and conveying anger at the civil and social injustices that she experienced in her lifetime.

“Revolution is not a one-time event; it is being always vigilant to the smallest opportunities to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses. For example, learning how to address each other’s differences with respect.”

The on-going theme through this talk for academics communicating research with any external organisation was that humility is key. Changing the language of the research is not the same as ‘dumbing down’ or oversimplifying; audiences, partners and collaborators are aware when this is happening. This is true of any discipline, and something to which the culture of academia is slowly adapting.

In conclusion

The speakers not only had genuine love for their research, but also the drive to make change happen. The London Scicomm Network exists as it does because it facilitates these changes; for every person present, there was someone else able to offer a solution, whether this was in terms of funding, connections, venues, or the sharing of best practice. Diverse and sustainable connections are essential, not just with our external collaborators, but also with other researchers and with impact and engagement support staff.

Revisiting the WHO Collaborating Centre aims, it is clear that the above lessons are important as we continue our journey of addressing key global health challenges from cultural perspectives. Answering critical questions concerning the creation and maintenance of health and well-being, particularly in relation to inequalities, requires us to engage with those with lived experiences; this will enable us to use narrative approaches that can take account of culture contexts more effectively and work together to create people-centred health systems. The cycle of public engagement should be integral to our own strategies moving forward, helping us to understand our duty to continually engage in order to create meaningful relationships and to generate measurable social, cultural and economic impacts.

For a look at some of the highlights of the day on Twitter you can check my Storify of #LSCS17

This post was written by Kerry Dungay, Project Manager, Cultural Contexts of Health