FORTY years ago, in a remote corner of the USSR, the World Health Organisation (WHO) adopted the Health for All declaration.

The declaration endorsed health as a human right and challenged health inequalities through a programme of primary health care, greater intersectoral action and community participation.

Last month, an Exeter University seminar considered the implications of this 1978 declaration and the role of key players – in particular, the previously unacknowledged part played by the Soviet Union.

Soviet sponsorship of the event provoked some commentators to describe the declaration as “a small Soviet victory” during the cold war, implying it was a triumph for an alternative, community-based approach to health in opposition to that of a more scientific, technical western medicine. But was it?

The ebbs and flows of the cold war have obscured the Soviet role in this story, compounded by shifts within – and between – the Soviet and WHO bureaucracies, as well as mutual misunderstandings about the meaning of a Health for All approach.

Health for All ideas were of increasing interest after World War 2 for many non-aligned countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. These countries sought a health model best suited to their needs and resources rather than the expensive and high-tech model of most western countries. All that was needed was a champion to promote this alternative approach.

Initially, WHO took the lead. Halfdan Mahler, the new director general appointed in 1973, sought to refocus priorities away from single diseases like malaria and polio to a broader – Health for All – approach. A new strategy was published and Health for All was adopted by the World Health Assembly (WHA) in 19772.

In the Soviet Union, health leaders envisaged a role for themselves in this emerging agenda, possibly as champions of the non-aligned movement. Even before the WHA meeting, they pressed WHO for an international Health for All conference.

The Soviet Union had always had an uneasy relationship with WHO. A founder member in 1948, it withdrew the following year unhappy with the organisation’s western orientation. Instead, it initiated bi-lateral health agreements with eastern bloc and non-aligned countries to promote its international role. It re-joined WHO in 1956 but continued with its twin-track approach to international health questions – both through WHO, and through bi-lateral co-operation outside WHO. Health for All was seen as a possible way of expanding Soviet international influence and settling cold war scores3.

It took the Soviet Union two attempts to succeed and secure WHO agreement for an international conference. Despite initial WHO reluctance, a second offer was accepted in 1976 backed by $2m on the basis that the conference would not be held in Moscow or Leningrad.

The 1978 Alma-Ata conference held in the Kazakh Soviet Republic generated considerable enthusiasm. Over 3,000 participants from many government and non-governmental organisations attended. Its shared agenda was politically grounded, scientifically sound and emphasised the inequalities between developed and developing nations. The declaration seems to have captured this spirit as a new, powerful voice for changing the world’s health priorities.

For the Soviet Union, a modest cold war triumph beckoned. It could seize the moral high ground as the sponsor of a new world health order that championed a cause of the non-aligned movement. Except, that the triumph failed to materialise. Why?

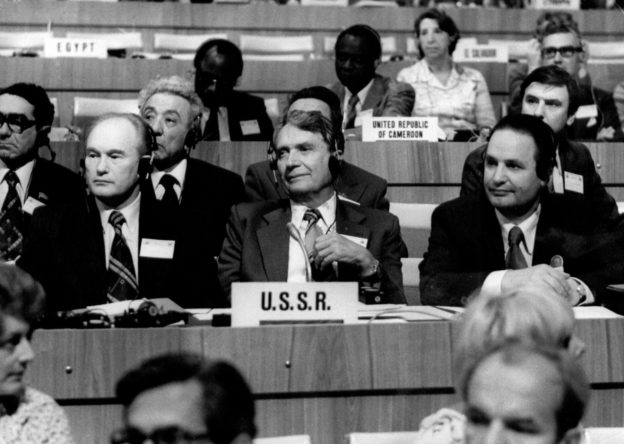

A key reason was the lukewarm attitude of the Soviet leadership. Neither Brezhnev, First Secretary of the Communist Party, or other senior party leaders, attended. The conference was not covered in the national party press, and it was left to local Kazakh leaders to showcase their health system with a programme of visits. In the event, Senator Ted Kennedy, the brother of the assassinated US President, filled the vacuum, won headlines despite not being part of the official US delegation.

It seems that Soviet leaders did not consider the event a significant ideological or political opportunity, notwithstanding advocates within the health ministry. Détente too, may have played a part in taking the edge off such ideological considerations.

Stealing conference headlines? – Senator Edward Kennedy and friend

Equally, the Health for All narrative sat uneasily with the Soviet perspective. They had no separate health vision. The local polyclinic concept, which on first sight seemed to align with WHO’s primary health care vision, was in reality far more centralised and controlled than anything advocated by the Health for All strategy.

Like western countries, the Soviet Union was more seized with the scientific and technical aspects of medicine than the primary health care/public health focus of the Health for All agenda. Where possible, they relished showing the superiority of the Soviet medical system. A telling comparison was the handling of the scientific International Congress of Genetics held in Moscow two weeks after Alma-Ata and feted by Soviet leaders.

There were mutual suspicions too between WHO and Soviet officials – with Soviet officials kept out of the key conference decisions. Perhaps this led the Soviets to underestimate the potential of the conference. These factors combined to give the Soviet Union a semi-detached attitude to Health for All – and to WHO. It meant that it ultimately reverted to its bilateral networks to promote the Soviet health system model – including through medical training – rather than tailor a separate approach for developing and non-aligned countries4.

After Alma-Ata

Although a Health for All approach found echoes in Canada and the UK through the Lalonde (1974) and Black (1980) reports, and in the 1986 WHO Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, there were powerful counter-veiling forces at work. The Rockefeller Foundation sought to narrow the Health for All focus. It advocated “selective primary health care” concentrated on childhood survival, which could show results and value for money. This approach coincided with wider economic and political changes in the 1980s, including the rise of neo-liberal policies, which sought to freeze WHO funds and reduce its reach, and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

However, judging whether the Alma-Ata declaration was a success or failure is the wrong approach, given the complications of the cold war. Even at the time, there were positives to be drawn for WHO.

For example, it achievements in community-based rehabilitation are not always well recognised. But, it was a WHO programme with social justice at its heart seeking to allow all disabled people to live a life in dignity5. Dramatic results have been achieved but are difficult to measure, which acts as a barrier to funding. Community engagement can also be tricky. Leadership is required from families and local professionals – rather than state or charity officials – to make the programme work well, reflecting the community participation principles of Health for All.

Realising Health for All objectives has proved elusive, not least because of the lack of systematic follow-up action by governments, yet the principles of Alma-Ata continue to resonate. The 2008 WHO Social Determinants of Health Commission report recognised that “social injustice is killing people on a grand scale”6. Primary health care remains a key policy aim with the adoption of ‘universal health coverage’ as a UN sustainable development goal (2015)7, and the renewal of these goals in the WHO Global Conference on Primary Health Care in Astana (October 2018)8.