It took Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) a trip to the past to figure out how best to deal with the future. Policymakers could do a lot worse than step back 20 years in time to reboot the Prime Minister’s commitment to reducing ‘the burning injustice’ of a nine-year gap in life expectancy between different areas of the country. Progress seems to have slowed almost to stop. If in doubt, ask Alan Milburn, Lord Adonis or even Justine Greening.

So, what’s the hold up? Is preoccupation with Brexit stifling action on other priorities? Are NHS reforms inadvertently undermining the national drive for a fairer society and healthier lives? Or are the social costs of austerity forcing society backwards by widening these and other inequalities?

Whatever the reason – and just like in the film – the dashboard on the DeLorean time machine needs to be reset. To 1998 – the year in which the Acheson inquiry report on health inequalities was published, and which kick-started action on the “link between income, inequality and poor health”.

Building a consensus for action

It needn’t be painful. Not least because a blueprint now exists to help avoid the rigours of time travel. The forthcoming WHO Europe report, The English Experience in Tackling Health Inequalities systematically sets out the lessons of the last 20 years and highlights England’s – and the UK’s role – as a global leader in addressing these inequalities.

Action in the past has not been straightforward and such inequalities were not always seen as amenable to policy intervention. As part of the ‘nature/nurture’ debate, action was often deemed counter-productive. Health inequalities – like the poor – were ‘always with us’.

Subsequently, it was also thought that a universal health service would address – automatically – the inequalities faced by previous generations. Awareness that the NHS could not do so on its own was slow to crystallise. Even when the harm resulting from health inequalities was set out – as in the Black report (1980) – the government found it hard to acknowledge or contemplate the costs involved in putting it right.

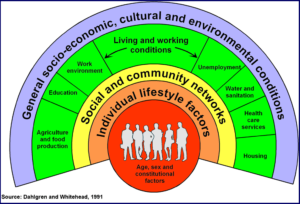

A change in the political climate in the 1990s recognised the link between health and wealth and allowed a full examination of the facts. The Acheson findings helped a new consensus to emerge around national targets and a national cross-government strategy, which recognised the impact of the social determinants of health. This approach achieved results. The health inequalities targets on infant mortality, cancer and cardiovascular disease were all met. The approach also came close to meeting the life expectancy target for males, while supporting a general improvement in life expectancy across all social groups.

Reducing health inequalities requires action across the wider determinants of health

The consensus culminated in the 2010 Marmot review. It made explicit the social gradient in health – where the lower a person’s social position, the worse his or her health. – and developed the concept of healthy life expectancy as an aid to policymaking. All parties recognised the value of the social gradient – and the need for proportionate action to reduce its steepness. The Coalition government endorsed the review findings and subsequently introduced the first-ever health inequalities duties, carried forward by the current government and NHS England.

Changing contexts for health: threat or opportunity?

This consensus faces several challenges. The impact of austerity on health and other public services has forced policymakers back to their core responsibilities, provoking a retreat from the kind of cross-government collaboration necessary to address the social determinants – the ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequalities.

This effect is reinforced by an increasingly NHS-centric approach to health. One result of the reforms is that key aspects of leadership have passed from ministers to NHS England, potentially narrowing the horizon for action, missing these wider connections and the full value of prevention and public health policies.

Likewise, the move from national to local decision-making since 2010 – “localism” – has permeated government policy and organisation, including the NHS. While there are new flexibilities in meeting local needs and priorities, there is less certainty about national health inequalities objectives and the means to achieve them.

Together, these changes – and the policy paralysis engendered by Brexit – may end up widening the health gap. Not least, between the local areas that have embraced the new opportunities and those that progress at a slower rate. It is a potential recipe for going even further back further in time – Back to the Future Part III anyone?. Pre-war days saw piecemeal services and a patchwork of variable health outcomes across the country, a long way from the hoped-for convergence arising from a social gradient approach generated by the new consensus.

Going back to the future to get things moving again

These challenges make it even more necessary to take stock of developments over the last 20 years. The evidence shows where to focus: on the social determinants, the main contributors to health inequalities, on unhealthy lifestyles, particularly smoking, and lastly on service inequalities.

Recent events have underlined the need for action. Until 2010, there were clear gains in life expectancy for all groups, suddenly this progress has stalled. Michael Marmot has calculated that the rate of increase in life expectancy has dropped by almost 50% since 2010. There are deepening concerns too about the lack of progress in creating a fairer Britain.

Now is the moment to revisit the lessons of the last 20 years. The WHO Europe guide to tackling the ‘burning injustices’ highlights the

- importance of evidence as a driver for action

- necessity of strategic leadership and partnership building

- need to embed action in government systems and structures

- develop of clear objectives, metrics and tools, and

- recognise that a long-term commitment and sustainable effort is needed to put these stubborn and persistent inequalities into reverse

We don’t have to start from scratch. Much material is close to hand that will help improve health and wellbeing and narrow the inequalities gap. So, while Back to the Future is good cinematic fare, learning these lessons will save time-travelling back to 1998 – with all the concomitant problems of getting back to the present. And, if you’re in any doubt, just watch the movie!

This post was written by Dr Ray Earwicker, honorary research fellow at the Centre for Medical History, University of Exeter, and formerly a senior policy adviser at the Department of Health.